DOC-IN-A-BOX

As a thought experiment, the Council on Foreign Relations' Global Health Program has conceived of Doc-in-a-Box, a prototype of a delivery system for the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. The idea is to convert abandoned shipping containers into compact transportable clinics suitable for use throughout the developing world.

Shipping containers are durable structures manufactured according to universal standardized specifications and are able to be transported practically anywhere via ships, railroads, and trucks. Because of trade imbalances, moreover, used containers are piling up at ports worldwide, abandoned for scrap. Engineers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute converted a sample used container into a prototype Doc-in-a-Box for about $5,000, including shipping. It was wired for electricity and fully lit and featured a water filtration system, a corrugated tin roofing system equipped with louvers for protection during inclement weather, a newly tiled floor, and conventional doors and windows. Given economies of scale and with the conversions performed in the developing world rather than

Staffed by paramedics, the boxes would be designed for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of all major infectious diseases. Each would be linked to a central hub via wireless communications, with its performance and inventory needs monitored by nurses and doctors.

Governments, donors, and NGOs could choose from a variety of models with customizable options, ordering paramedic training modules, supplies, and systems-management equipment as needed. Doc-in-a-Boxes could operate under a franchise model, with the paramedics involved realizing profits based on the volume and quality of their operations. Franchises could be located in areas now grossly underserved by health clinics and hospitals, thus extending health-care opportunities without generating competitive pressure for existing facilities.

On a global scale, with tens of thousands of Doc-in-a-Boxes in place, the system would be able to track and respond to changing needs on the ground. It would generate incentives to pull rapid diagnostics, easy-to-take medicines, new types of vaccines, and novel prevention tools out of the pipelines of biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies. Supplies could be purchased in bulk, guaranteeing low per-unit costs. And the sorts of Fortune 500 companies that now belong to the Global Business Coalition on HIV/ AIDS, TB, and Malaria would be able to provide services and advice.

Over time, Doc-in-a-Boxes could emerge as sustainable local businesses, providing desperately needed health-care services to poor communities while generating investment and employment, like branches of Starbucks or McDonald's.

The Doc-in-a-Box Plan

STEP ONE: The Box

Shipping containers are standardized, designed specifically to make transport as efficient and simple as possible. Intended to be stacked, with each individual container able to withstand millions of kilos of weight from atop, they are virtually indestructible. Because container shipping often requires stacking the units atop a ship deck, rail car or 18-wheeler truck they can withstand all possible weather conditions and salt water. Further, the containers have features specifically aimed at making them easy to lift with cranes or helicopters, attach to rail cars, clamp onto diesel truck beds and stand on deceptively small steel legs, their bottoms not touching wet or snow-bound grounds.

to withstand millions of kilos of weight from atop, they are virtually indestructible. Because container shipping often requires stacking the units atop a ship deck, rail car or 18-wheeler truck they can withstand all possible weather conditions and salt water. Further, the containers have features specifically aimed at making them easy to lift with cranes or helicopters, attach to rail cars, clamp onto diesel truck beds and stand on deceptively small steel legs, their bottoms not touching wet or snow-bound grounds.

These features ensure that containers can be:

- shipped anywhere in the world

- transported from ports into any areas accessible by rail or road

- from there, if necessary, transported further by helicopter to even extraordinarily remote locations;

- stacked as modules to form larger structures;

- left in place for more than three decades without concern of deterioration, breeching the integrity of walls, roof and floor.

The container industry, further, manufactures standardized “flat racks” and “tweendecks”, upon which containers can rest, providing a stable platform that further separates the box from ground surfaces. So-called “reefer” containers that are intended for transport of food stuffs have built-in refrigeration units, allowing for either cooling or heating the airspace.

Australian architect Sean Goodsall developed a container prototype for housing Kosovar refugees. Now on exhibit at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Center in New York City, “Future Shack”, as Goodsall dubbed it, is powered by two small solar panels mounted on its roof and features kitchen, bath and living facilities. American architect Adam Kalkin sells chic prefab houses made from stacks of retrofitted containers, priced at about $73/sq foot. (See column to the right for URL list and attached photo display with more examples of architectural use of containers.)

An organization called Global Peace Containers, a nonprofit based in the

The Doc-in-a-Box Plan

STEP TWO: Inside the Box

Welcome to an instant primary care outpatient clinic, staffed daily by one or two paramedics drawn from the local community and trained to conduct saliva-based tests for TB, HIV, hepatitis and malaria; dispense drugs for said diseases; administer childhood vaccines; dispense condoms; hand out sterile syringes to IV drug users (where appropriate to regional epidemiology); offer basic information about prevention of a finite list of infectious diseases; and refer patients with other illnesses or trauma injuries to doctor-staffed clinics or hospitals.

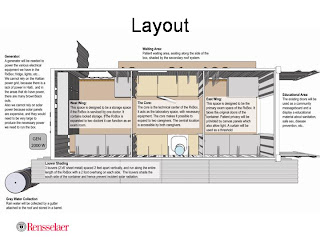

Located anywhere, from a desperate urban slum to a sparsely populated remote rural village, these retrofitted shipping containers, cum Doc-in-a-Boxes, contain a patient intake room; two gender-specific examination rooms; a staff room with a small solar-powered fridge for vaccines and heat-sensitive medicines and diagnostics; storage and a space for processing simple saliva-based tests. All child vaccines are administered exclusively with auto-destruct syringes, and the paramedics would never use other syringes or come in contact with blood for diagnosis or treatment.

The Doc-in-a-Box is for people who think they are well, in addition to those who are experiencing symptoms. Every individual is photographed, using a computer-mounted camera, and a badge is made bearing the photo and a bar code. The badge is laminated, and given to the individual: it is taken proudly by many, as it is the only photo they may have of themselves. Every time the individual returns to this, or any Doc-in-a-Box the bar code swipe will reveal to the health provider the following information:

- patient name, age, date of birth, place of birth, name of parents (for children) and spouse

- patient vaccination history, especially noting any recent immunizations and outstanding boosters or lapsed protection

- dates of recent tests and physical exams (for HIV, TB, malaria, syphilis, gonorrhea) and their results

- lists of medicines given to the patient (for TB, malaria, HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea) and dates dispensed

- note whether preventive tools were dispensed, and if so when and in what quantity (bed nets, condoms, educational pamphlets, sterile needles to IDUs

- treatment outcome, where appropriate

- history of referral, noting date of referral and reason (or suspected diagnosis)

- in pediatric cases, parent’s names and health status

- for adults, mate’s health status, if known

(Note: where confidentiality concerns might raise issues about name-associated data, patients could create easy-to-recall nicknames for themselves, or alternative identities to be entered in bar codes.)

The computer system inside each Doc-in-a-Box would be very simply, not have access to the Internet, have no utility outside the Doc-in-a-Box setting and therefore not be worth stealing. The computer would be designed with heat tolerance and ease of repair and maintenance in mind. It would operate on solar-powered electricity, except where alternative power supplies are cheap and readily available. Its functions would include bar-code processing (as listed above) and data storage. The utility of that data for tracking local disease trends and research purposes is obvious, and would be limited only by research interest and locally determined ethical constraints. Obviously, widespread distribution of Doc-in-a-Boxes would constitute the largest basic health database ever assembled in developing countries, might take the guesswork out of regional epidemiology (for HIV, malaria, TB and STDs) and could offer real time warnings of emergence of resistant microbes in the form of trends in clinical failures. Data from the individual Doc-in-a-Box computers could be collected on a routine basis by Ministry of Health personnel, using simply USB jump drives, and fed into a centralized, redundant system.

Everything the Doc-in-the-Box requires would arrive, already installed, in a fully outfitted container. This would include office furniture, electrical wiring (hooked to the solar power or other source), plumbing (hooked up either to local supply, rainwater cachement system or other local source to be determined), and modest lab facilities. Wherever possible furniture and equipment would be installed in a manner to defy easy theft, and potentially valuable pipes and wiring would be sealed behind insulating walls

Because the Doc-in-a-Box is made of completely standardized modules, the contents and medicines can also be standardized and bulk purchased. This standardization ought to both bring down costs and offer R&D incentive to profit-based industry for development of still better diagnostic and treatment tools. As noted above, it is imperative that such local clinics shun diagnostics based on blood, as nosocomial transmission of blood borne disease has proven a predictable constant in resource-scarce settings. Simple “toothbrush tests” – diagnostics based on saliva, mouth scrapings or genital swabs– should be the norm for all screenings in Doc-in-a-Boxes. These tests should strive to be as close as possible, in simplicity and accuracy, to a Litmus pH test.

From the outside a Doc-in-a-Box would be brightly colored and attractive, with windows and an entry cut strategically in the original containers. The number of containers necessary to form any individual Doc-in-a-Box could reflect local needs and finances: a standard 8’X20’ container, with only 160 sq feet, could hardly handle the above-described needs. Even the larger 8’X40’ containers, at 320 sq feet, would be too small for most needs. The beauty of the container approach, however, is that modules can be added as needed, stacked horizontally in rural areas, vertically in urban.

Simple overhangs or roofs spanning spaces between containers could provide shaded waiting areas. Prefab playground equipment, such as the Ronald McDonald set-ups located outside American fast food eateries, could provide kids with entertainment while parents undergo exams. It is anticipated that in many communities the Doc-in-a-Box would become a nexus of social activity, further heightening a sense of community ownership and pride.

The Doc-in-a-Box Plan

STEP THREE: Building the Box

Because of the standardization of the Doc-in-a-Box modules, and their ease of transport, the clinics could be retrofitted on a high thru-put, mass scale in a port city, preferably in a developing country.

Because hundreds of thousands of containers languish in ports around the world it seems reasonable to assume necessary units could be had – even delivered to a retrofitting center – for free. A combination of tax incentives and political pressure from such organizations as the Global Business Coalition on AIDS, Global Fund and World Bank might well induce the shipping industry to donate not only empty containers, but also their transport to a designated production port.

There are many companies in the world that already carry out container retrofitting and others that might be interested in such a project. History shows that production on large scale is best executed by a for-profit industry. Given the containers could probably be had either for free, or at less than $600/apiece, completely retrofitting units ought to be feasible for less than $5,000/each, particularly if made in a developing country. If a company charged $6,000/module it would realize a 20% profit, in this theoretical model.

Because simplicity is elegance, as stated above, only a finite range of perhaps a dozen modular options would be manufactured, offering potential purchasers (Ministries of Health, NGOs, etc.) a finite menu from which to select options for their Doc-in-a-Box needs.

The Doc-in-a-Box Plan

STEP FOUR: Delivering the Box

Because, as I have repeatedly underscored, containers are designed for transport, their delivery to even remote areas should be doable, even easy. Ships, trains and trucks need to be coordinated in careful logistics choreography. Once again, there are numerous companies in the world that specialize in such logistics; ideally a global industry working with regional partners could be recruited. A combination of economic efficiency and good global negotiations ought to keep delivery costs down to manageable proportions.

At the local level two steps ensure that the community is ready to receive its Doc-in-a-Box. First, local individuals would be selected for health care training. After undergoing their standardized, modular training sessions for operating a Doc-in-a-Box, these individuals would discuss the purposes of the forthcoming clinics with their friends and neighbors. And secondly, an actual location for the clinic would have to be selected and prepared for the containers’ arrival. To the degree the community is drawn into the process of preparing for its Doc-in-a-Box, it is more likely to feel pride of ownership, and make appropriate use of the facility.

The Doc-in-a-Box Plan

STEP FIVE: Managing the Box

Accountability, in some form or another, is the number one concern voiced by critics of the new global health initiatives. In their current forms these programs try to track donations of money and goods by monitoring the activities of receiving Ministries of Health or NGOs. This is currently a difficult process as every local program is unique, systems for tracing medication storage and dispersal are virtually nonexistent and activities and personnel tend to aggregate in national capitals and major cities, leaving rural areas out of the loop. Bluntly speaking, programs are amorphous and vague. It is nearly impossible for average citizens to understand how money is – or is not – being spent. Further, many NGOs that have received money from the Global Fund or other initiatives have no history in large scale implementation, bookkeeping and accountability. As Gonsalves asked the

There is nothing amorphous or intangible, however, about a Doc-in-a-Box. It either exists in a community, or does not. It is either staffed competently, or it is not. Photographed, bar code entered patients either undergo medical tests and receive appropriate medicines, or they do not. If the community, itself, feels a sense of ownership of its Doc-in-a-Box it will demand that services are maintained.

Let me give you an example: “Yesterday”, a Zulu-language film scheduled to air in a few months on HBO. The heart-wrenching feature film tells the tale of a man, woman and their little girl in KwaZulu Natal, fighting personal battles against HIV. Repeatedly the woman, named Yesterday, and her little girl walk many miles to the nearest medical clinic, stand for hours waiting, only to be told the doctor can see no more patients. Yesterday and her daughter stagger the long way home. When, after three visits, Yesterday finally manages to see a doctor she is told that she has HIV, and no medicine is available. Tragically – as is the case today for 95 percent of all HIV+ people in the world – Yesterday and her husband die having never received a single HAART drug.

When I watched Yesterday’s story I thought of the hundreds of towns and villages I have visited since I started covering HIV in 1981 and realized that had her KwaZulu village had a Doc-in-the-Box there would have been no story to tell. Instead of dying, Yesterday would have learned on her first visit that she had HIV, and received both life-sparing drugs and condoms. Her secret – if it need be so – would have been known only to the health care worker and herself. Beyond that, it would have been up to Yesterday to decide how she would go on with her life, whether her missing husband need know, what sort of precautionary future she might create for her daughter and whether any of her extended family or neighbors need know of her illness.

I have no doubt that a community of “Yesterdays”, whether they individually suffered from malaria, HIV, TB or other diseases monitored in Doc-in-a-Boxes, would fight to save their clinics and demand that they offer top quality care.

Routine maintenance and accounting could be handled by a combination of NGO and government services. Again, because of standardization of all modules and contents, spare parts and methods for monitoring medication use could be routinized, and government and civil society could watchdog one another.

The Doc-in-a-Box Plan

STEP SIX: Financing the Box

A mixed system of global health financing is already in place. The Doc-in-a-Box scheme would require start-up funds for prototype development and factory scale-up. But thereafter, manufacture, sale and delivery of Doc-in-a-Boxes would be covered by the existing finance schemes. Doc-in-a-Boxes could be ordered and staffed by Ministries of Health, NGOs, local community governments, religious groups, local companies and employers, universities and other public entities. A would-be Doc-in-a-Box purchaser would petition for funds to cover costs of health care worker training, salaries and module purchase and delivery in the same manner that they now petition for other health-related money.

The Doc-in-a-Box Plan

STEP SEVEN: Research in the Box

As mentioned above the Doc-in-a-Box system could result in the largest primary health database in the world. This would have obvious research utility, within ethical constraints. In addition to its epidemiological value (including, for the first time, offering accurate estimates of HIV, TB and malaria contagion community-by-community), the Doc-in-a-Box system could provide means for comparing various treatment protocols, trying new therapies and testing vaccines. In a very real sense The Doc-in-a-Box Plan integrates treatment, prevention and basic research.